Africa's Virtual Water Trade

Virtual water refers to the water that is ‘hidden’ or embedded in products of consumption such as food or textiles. In terms of food, it is the precipitation (green water) or irrigation water (blue water) used to grow crops, the water used for harvests, the water used to clean and remove dirt from produce, and the water used to transport food to its destination. Global virtual water flows of traded agricultural and industrial products were 2,320 Gm3/year between 1996 and 2005. 76% of this virtual water flow was the international trade of crops or crop derived products (Hoekstra and Mekonnen, 2012). Why is virtual water important and how does it relate to countries in Africa?

Figure 1 – Virtual water (VW) imports and

exports of major grains between Africa and its trading partners from 2000 to

2020. Values shown are quantified in Bm3 (Hirwa et al., 2022).

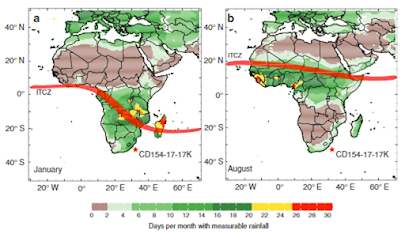

As mentioned in the previous

blogs, water scarcity is already threatening the population of Africa and

climate change is causing varied patterns of precipitation, significantly straining

countries’ agricultural systems and their ability to feed a growing population.

In order to survive these conditions, farmers have to be smart about the crops

they grow and the food they import. For example, 1827 litres of water is needed

to produce a kilogram of wheat but 287 litres of water is needed to grow a

kilogram of potatoes (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2011). The trading of these goods

is essentially the trading of virtual water, so to maintain food security under

conditions of water scarcity and stress, nations within Africa should import water

intensive cereal crops, but grow and export less water consuming crops to

conserve water (Wu et al., 2022). Figure 1 demonstrates this argument

and idea through visualising Africa’s virtual water imports and exports. Africa

imports a total of 2170 Bm3 of water whilst exporting only 80 Bm3

of water. This means that Africa conserves a net volume of 2090 Bm3

of water.

Focusing on Kenya:

Water scarcity and

stress and are serious issues in Kenya that have been existent for decades. Drought

conditions over the past two years have been fatal to Kenya’s blue water sites

of storage, where 80% to 90% of Kenya’s reservoirs and dams have dried up. This

has had knock on effects causing the death of 1.4 million animals and leaving limited irrigation water for agriculture. In situations such as these, residents can

only rely on imports of water intensive cereal crops such as barley and wheat,

whilst being encouraged to grow less water intensive crops.

Figure 2 – Change in Kenya's production, imports and exports of cereal crops, coffee and tea (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2014).

However, Kenya’s economy

and livelihood relies on the unsustainable use of water to grow food crops such

as maize or coffee which both have large water footprints (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2014). Agriculture contributes to 33% of the country’s GDP, with

Maize forming 12% of this agricultural GDP and coffee contributing 100 billion Kenyan Shillings or roughly £670 million, to Kenya’s economy from 2001 to 2011.

Undoubtedly, these high-value crops form the core of Kenya’s agricultural

sector. Nonetheless, these patterns of production cannot be sustained as water scarcity

intensifies under drought conditions and climate change. This is the reason why

Kenya has shifted to importing over 25% of the country’s cereal products,

whilst also increasing exportation of less water intensive crops such as tea

and interestingly, cut flowers (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2014). Cut flowers, despite

using up to 13 litres of water to grow one rose and contributing to pollution

in Lake Naivasha, remain important parts of the economy, generating US $353

million in 2005 (Mekonnen et al., 2012). Such a strategy would conserve

water for other uses and increase water productivity and cost-efficiency in the

long run.

Whilst Kenya’s strategy

and solution sounds economically and environmentally effective, it is important

to bear in mind that a heavy reliance on importing food can actually be detrimental for food security at times of crises, such the COVID-19 crisis,

where production, trade and logistical systems failed, resulting in panic

buying or exacerbated food prices. Moreover, global pressure on fresh water

resources will increase, so constantly growing water-intense crops such as

wheat or rice becomes unsustainable. Water productivity has to increase to

produce large yields of these crops and policies must exist to sustainably

manage water resources and their quality (Mekonnen and Hoekstra, 2020).

Comments

Post a Comment