Small Scale VS Large Scale Commercial Agriculture

Agriculture can form a central part of the economy for many African nations. An example is Sierra Leone and how 58% of its GDP is dominated by agriculture. Agriculture across Africa also varies in scale, power and size ranging from small scale subsistence farms to large scale commercial plantations. Currently, approximately 33 million small scale farms exist across Africa, contributing to 70% of Africa’s food supply. However, the presence and existence of medium or large scale farms between 5 to 100 hectares are also increasing, but they do not exist in the magnitude that small scale farms exist. Often, these large scale farms are criticised for not contributing to food security within Africa, but instead leaving disastrous environmental and social impacts in their wake.

Small scale farms

have often been seen as the drivers of growth across Africa, providing food for

local communities but also employing and managing a large labour force; 175 million people are directly employed by smallholder farms in Sub-Saharan Africa. They are seen to be very valuable where farmers possess knowledges of

local environments and climates, which inform their decisions on crop growth

and maintenance, but can also be used to create ‘climate-smart agricultural

innovations’ to support local communities and build climate resilience (Makate, 2020: 277).

Moreover, small

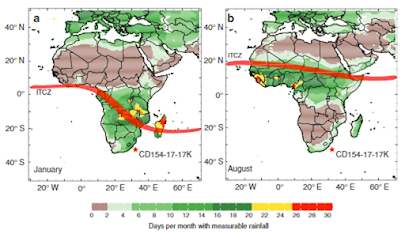

holder farms also use water less intensively in comparison to their large scale

counterparts, as farms are typically smaller than a hectare and often rely on precipitation

to grow crops. Small holder farms also create local irrigation technologies and

initiatives, such as furrow irrigation or using shallow groundwater in valley

bottoms to maintain their agricultural production (Woodhouse et al.,

2016). For some, they remain Africa’s main asset, whilst others contest them

and recommend the upscaling and commercialisation of agriculture.

To achieve

development goals and further increase economic growth, some believe that there

is a need to shift focus and resources away from smallholder farms and

re-direct these efforts to create opportunities for ‘megafarms’ to increase

productivity (Collier and Dercon, 2014: 99). Whilst these large scale farms may

possess scientific knowledge or receive greater funding than smallholder farms,

empirical evidence shows that they can actually have dire consequences on local

environments and small scale farmers. In order to make space for these large

farms, deforestation is a process that usually occurs which reduces tree cover directly.

9.4% of trees were lost in Mozambique between 2000 and 2015 as a result of large scale farms (Zaehringer et al., 2021). Large scale farms have also been accused of ‘water

grabbing’ or trying to secure control of local water resources such as rivers,

lakes or aquifers and reduce flow and access to local communities and small

scale farmers (Breu et al., 2016). Whilst these large scale farms may be

useful for improving global food security, they pose risks for local food

security by outcompeting other farmers. Thus exists the high controversies of adopting

commercialised large-scale farms in Africa.

Following

Schumacher’s (1973) message of ‘small is beautiful’, perhaps small scale farms

are Africa’s best solutions to maintain food security and local environments. Large

scale farms and the commercialisation of agriculture is something that will be observed

more in the future, but to reduce their consequences and make them tools for

positive change, owners should work with local people and their knowledges to understand the geology and geographies of environments and support local food security.

Comments

Post a Comment